LEUKAEMIA

Here we provide facts about leukaemia, explaining what type of blood cell cancer it is and include terminology that haematologists use when diagnosing leukaemia and discussing treatment options.

CONTENTS

- What is leukaemia?

- What causes leukaemia?

- How do I know that I have leukaemia?

- What are the main types of leukaemia?

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)

- Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

- Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)

- Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML)

- Uncommon types of leukaemia

- Hairy cell leukaemia (HCL)

- Large granular lymphocytic leukaemia (LGL leukaemia)

- Plasma cell leukaemia (PCL)

WHAT IS LEUKAEMIA?

Leukaemia is not a single disease but a group of malignant disorders - cancers that affect blood and bone marrow cells. Blood cells originate from stem cells in the bone marrow. When stem cells divide they create lymphoid precursor cells and myeloid precursor cells. Lymphoid precursor cells develop into lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) and myeloid precursor cells go on to form red blood cells, platelets, and two types of white cell, namely monocytes and granulocytes. When myeloid precursor cells fail to develop properly people may develop a myeloid leukaemia. Similarly abnormal lymphoid precursor cell development may rise to lymphoblastic or lymphocytic leukaemia.

WHAT CAUSES LEUKAEMIA?

The reason why most people develop leukaemia is unknown. Exposure to certain chemicals such as benzene or to radiation may contribute to the development of leukaemia. This includes people previously treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Some forms of leukaemia are also more common in smokers. Leukaemia is not a contagious disease. Although chromosomes of leukaemic cells can be abnormal, leukaemia does not get passed directly from parents to their children. However, some forms of leukaemia are more common in close relatives of people affected with this type of cancer, for example parents, siblings, or children of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia have more than twice the risk of developing the condition. Some other very rare diseases may predispose to development of leukaemia, some of them are inherited and run in families.

HOW DO I KNOW I HAVE LEUKAEMIA?

Laboratory tests are essential for diagnosing leukaemia. In many cases leukaemia is diagnosed from routine blood tests, when the doctor ordering the test does not suspect it.

This is because leukaemia can cause vague symptoms such as tiredness, sleepiness or headaches. Occasionally there may be blurred vision or gum bleeding. Tiny red spots on the skin or easy bruising are sometimes the first sign of leukaemia. Fevers, frequent or severe infections due to the low immunity associated with leukaemia may lead to the diagnosis. Some patients develop pains in bones or joints and sometimes patients notice swollen lymph nodes or abdomen. Unexplained weight loss can rarely be also due to leukaemia.

WHAT ARE THE MAIN TYPES OF LEUKAEMIA?

There are many types of leukaemia, some are fast growing - acute leukaemias and others develop more slowly - chronic leukaemias. To deliver correct treatment it is important to establish the exact type of leukaemia, as each type is treated differently. The following are the most common types of leukaemia:

ACUTE LYMPHOBLASTIC LEUKAEMIA (ALL)

This is a malignant disorder (or cancer) of lymphoid precursor cells, called also lymphoblasts. Normally lymphoblasts mature into lymphocytes - important white cells involved in fighting infection. However in ALL, immature lymphoblasts quickly accumulate in the bone marrow. Sometimes they spread into the blood, spleen, lymph nodes, and occasionally into spinal fluid.

These abnormal leukaemic lymphoblasts build up in the bone marrow, preventing normal blood cell formation. As a result there are not enough normal white blood cells, red blood cells, or platelets. The lack of white cells predisposes to infections; insufficient red cells causes anaemia, with symptoms of shortness of breath and tiredness. Low platelets may predispose to easy bleeding and bruising.

There are different subtypes of ALL. The two main groups relate to the lymphocyte subtype; these are known as B cells and T cells. These can be discriminated by examining the patterns of proteins on surfaces of leukaemic cells using immunophenotyping. Most people with ALL will have B cell or T cell type. Occasionally people may have other rare types. Other distinct subtypes are identified by analysing alterations in chromosomes and genes of affected leukaemic cells. Some of these subtypes, such as acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

ALL is more common in children than in adults, but it can occur at any age. In adults it is seen at both extremes of age. In general children have higher rates of cure, but prognosis is otherwise variable and dependent on the type of ALL and response to therapy.

ALL develops fast and therefore treatment must commence promptly. Therapy is complex and lengthy. In younger patients the aim is to achieve cure, in elderly people or people with significant other health problems this may not be possible and the aim is to prolong meaningful life. Therapy consists of anti-cancer therapy, timely treatment of infections and also supportive care, which includes providing red cell and platelet transfusions. The anti-cancer treatments include chemotherapy sometimes alongside targeted anti-leukaemic therapy or immunotherapy including allogeneic bone marrow transplantation

ACUTE MYELOID LEUKAEMIA (AML)

This is a malignant disorder (or cancer) of myeloid precursor cells, called also myeloblasts. Normally myeloblasts mature into red blood cells, platelets, or the white cell types called monocytes and granulocytes. Cell formation is abnormal in this type of leukaemia and myeloblasts accumulate in the bone marrow. Sometimes they go also into blood and occasionally into other organs, commonly into spleen, or liver.

These abnormal leukaemic myeloblasts very quickly build up in the bone marrow, preventing normal cell development. As a result there are not enough normal white blood cells, red blood cells, or platelets. The lack of white cells predisposes to infections; insufficient red cells causes anaemia, with symptoms of shortness of breath and tiredness. Low platelets may predispose to easy bleeding and bruising.

There are different subtypes of AML. Some, such as acute promyelocytic leukaemia can be distinguished by looking at the bone marrow cells under the microscope. For other subtypes of AML special testing is required, such as testing for changes in the genes of affected cells. Acute promyelocytic leukaemia has a specific therapy which includes administration of a very potent form of vitamin A – tretinoin, together with chemotherapy. For other forms of AML, initial therapy is usually similar and then is tailored by specific subtype.

The reason why most people develop acute myeloid leukaemia is unknown. Exposure to certain chemicals such as benzene or to radiation may contribute to development of leukaemia. This includes people previously treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Acute myeloid leukaemia is also slightly more common in smokers. It is not a contagious disease. Although chromosomes of leukaemic cells can be abnormal, leukaemia does not get passed directly from parents to their children.

Acute myeloid leukaemia can occur at any age but the risk increases with age; it is therefore most common in elderly people. In general younger patients have higher curative success rates, but exact predictions of success of therapy are very complex.

Treatment of acute myeloid leukaemia is a complex and lengthy procedure. In younger patients the aim is to achieve cure. In elderly people or people with significant other health problems this may not be possible and the aim is to prolong meaningful life. Therapy has two main components; supportive care, which includes providing red cell and platelet transfusions and prompt treatment of infections and secondly the systemic anti-cancer therapy. This includes administration of chemotherapy sometimes combined with targeted anti-leukaemic therapy or immunotherapy including allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.

CHRONIC LYMPHOCYTIC LEUKAEMIA (CLL)

This is a malignant disorder (or cancer) arising from lymphocytes – one of the two main types of white cells. This is the most common type of leukaemia. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia usually affects older people and both develops and grows slowly. The leukaemic lymphocytes can accumulate in the bone marrow, lymph nodes or spleen. They also appear in blood where they look similar to normal lymphocytes. This type of leukaemia is very often diagnosed in people who do not feel unwell and is picked up by routine blood tests. Some people notice enlarged lymph nodes - lumps in the neck, armpits, groins or elsewhere. Sometimes patients may feel tired, experience weight loss or heavy night sweats. CLL can impair the body’s ability to fight infection, so patients may have more frequent infective illnesses.

The exact cause of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is unknown, however risk factors include age. This leukaemia is more common after the age of 60 and very rare before 40. Genetics also play an important role and people who have a sibling or a parent with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia have significantly higher chance to develop it. We also see more of this type of leukaemia in relatives of patients with lymphoma.

Many patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia do not need any treatment and doctors monitor their clinical condition and blood tests. This “watchful waiting” does not in any way worsen overall outlook and outcomes of further treatment. If treatment is required it usually consists of oral chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy (antibodies). This treatment typically controls CLL, but does not cure it. After some time the leukaemia may return and new, often different, chemotherapy is required. New anti-leukaemic drugs have been developed that do not have the typical side effects of chemotherapy and they are sometimes referred to as targeted therapy. They are very useful when chronic lymphocytic leukaemia does not respond to chemotherapy well. Occasionally bone marrow or stem cell transplantation may be considered and this can cure this leukaemia. It is used rarely due to its side effects and due to the success of other above mentioned treatment options.

CHRONIC MYELOID LEUKAEMIA (CML)

This is a malignant disorder (or cancer) of bone marrow stem cells. In chronic myeloid leukaemia cell production becomes unregulated and myeloid precursor cells develop in excess. This overproduction takes lots of energy, so patients with this type of leukaemia often complain of tiredness and weight loss.

These abnormal leukaemic cells build up in the bone marrow, preventing normal blood cell formation. As a result there are not enough normal white blood cells, red blood cells, or platelets. The lack of white cells predisposes to infections; insufficient red cells causes anaemia, with symptoms of shortness of breath and tiredness. Low platelets may predispose to easy bleeding and bruising.

After the bone marrow gets filled with leukaemic cells they also start filling the spleen. Consequently the spleen enlarges, sometimes causing pain or discomfort as it fills the abdomen. High numbers of white cells in the blood can occasionally block small blood vessels, causing problems, such as blurred vision or rarely in men it can lead to uncontrolled erection of the penis.

Chronic myeloid leukaemia can develop at any age and as with other leukaemias the exact cause is unknown. Exposure to some chemicals such as benzene or to radiation is known to increase its risk. Chronic myeloid leukaemia cells carry an abnormal chromosome known as the Philadelphia chromosome, made from an abnormal fusion of chromosomes 9 and 22. It brings together two genes BCR and ABL1, making one abnormal gene known as BCR-ABL1. Consequently leukaemic cells make a new abnormal protein. Modern cytogenetic techniques are used to detect BCR-ABL1 gene.

Drugs that can stop the function of the new abnormal protein have been developed and they can control leukaemia. They have completely revolutionised the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia and are known as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, sometimes called targeted therapy. While on these drugs, it is essential to monitor the blood for the presence of residual leukaemia, as sometimes these drugs lose control over leukaemia. If this happens a different can be used. Sometimes this is not possible and then bone marrow or stem cell transplantation is considered to cure this leukaemia. In some people taking tyrosine kinase inhibitors for several years such a good response can be achieved that the drug can be carefully stopped.

Without treatment chronic myeloid leukaemia would always progress into what closely resembles acute leukaemia It only happens only extremely rarely while patients are on tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. This process is known as blastic transformation and can carry a poor prognosis, although in some cases chemotherapy followed by transplantation can help.

CHRONIC MYELOMONOCYTIC LEUKAEMIA (CMML)

This is a malignant disorder (or cancer) of myeloid precursor cells, called also myeloblasts.

In this leukaemia myleloblasts cannot develop into normal blood cells. Instead they tend to produce many abnormal subtypes, known as monocytes and also granulocytes. The blood count therefore shows more monocytes in blood and often also increased granulocyte counts. This makes infections more common and more difficult to treat. Usually chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia develops slowly but occasionally it can deteriorate quickly.

The danger of chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia is that it may progress into acute myeloid leukaemia, with very many primitive blast cells in the blood or bone marrow. The outlook is poor in patients who have developed acute leukaemia from chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia.

The treatment of chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia is supportive with red cell transfusions if needed and with administration of drugs that reduce white cell counts, such as hydroxycarbamide (also known as hydroxyurea). Sometimes erythropoietin, a growth factor, can be given as a injection under the skin to help with red cell production and reduce the need for red cell transfusions. Prompt treatment of infections is also important. There are also drugs that can in some patients get this disease under control. These are azacitidine given under the skin and decitabine given into the vein. Unfortunately only about a third of patients respond to this treatment. Currently no drug can cure chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia, the only creative treatment is allogeneic bone marrow (haematopoietic stem cell) transplantation. This leukaemia usually affects older people and transplantation, which is a very intensive treatment, may therefore not be possible.

UNCOMMON TYPES OF LEUKAEMIA

There are other uncommon types of leukaemia:

-

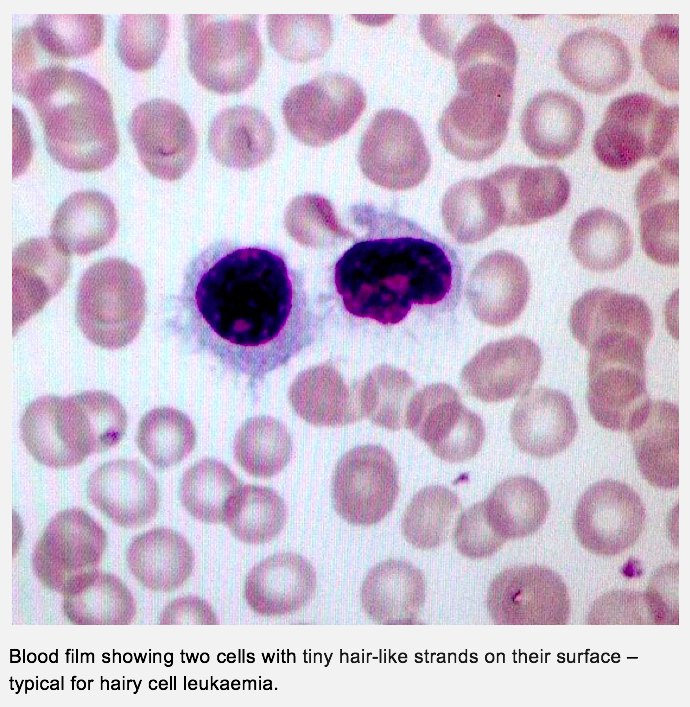

- Hairy cell leukaemia (HCL) – this is a rare type of leukaemia that affects lymphoid precursor cells. When examined under the microscope the leukaemic cells appear to have tiny hair-like strands on their surface. This leukaemia develops very slowly and often enlarges the spleen. Hairy cell leukaemia sometimes may not need any treatment. If treatment is needed, chemotherapy given into the vein is used: cladribine (2-chloro-deoxy adenosine) or pentostatin (deoxycoformycin) are good and long-lasting control of hairy cell leukaemia.

-

- Large granular lymphocytic leukaemia (LGL leukaemia) – this is a rare type of leukaemia that affects lymphocytes. Blood and bone marrow examination shows enlarged lymphocytes with granules. There are two main forms, an aggressive type that is very rare and may developed quickly and a chronic, slowly developing form. Patients with the aggressive type may develop enlargement of the liver, spleen or lymph nodes. As this leukaemia is extremely rare, there is no standard generally agreed treatment but intensive chemotherapy is recommended, sometimes followed by bone marrow (haematopoietic stem cell transplantation). However, most patients affected with LGL leukaemia will have a chronic, slowly developing form. They may experience no problems. Low red cell count (anaemia) or low neutrophil count (neutropenia) are common. Sometimes patients develop an enlarged spleen. Many patients with this chronic form do not require any therapy. Large granular lymphocytic leukaemia develops more often in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In this context the leukaemia responds to treatment with immunosuppression. Intravenous chemotherapy may sometimes be useful.

-

- Plasma cell leukaemia (PCL) – this is a very rare type of leukaemia. It is very similar to a blood cancer called multiple myeloma. The affected cells in both plasma cell leukaemia and multiple myeloma are related to lymphocytes and are called plasma cells, which normally make antibodies. Signs and symptoms are similar to those in myeloma and this link leads to more information.

For more information about leukaemia try following link: Blood Cancer UK